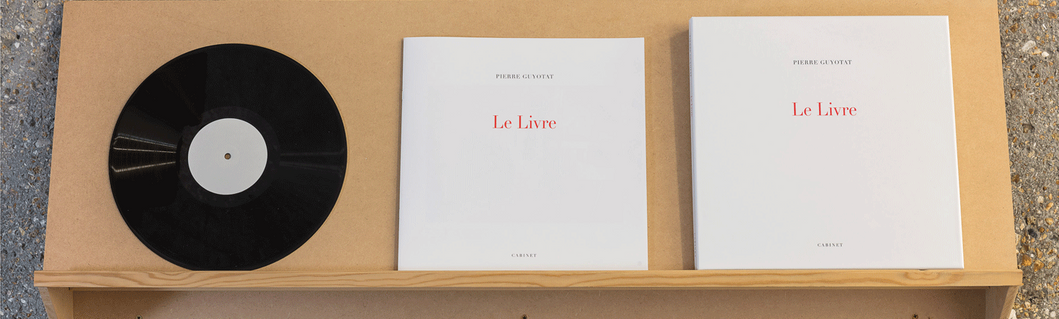

You know your writing is extreme when Jean Genet is the voice of respectability campaigning against the censorship of your book. In 1970, Genet was amongst a number of intellectuals to sign a letter protesting the French government’s ban on Pierre Guyotat’s second novel, Eden Eden Eden (1970) – a scandal that secured the author’s reputation as a literary outlaw and, according to Edmund White, ‘the last great avant-garde visionary of the 20th century’. Cabinet’s second exhibition with Guyotat

is accompanied by a fresh translation of the book alongside previously unreleased audio recordings and a new suite of drawings. A hallucinatory evocation of the horrors of colonial sexual violence, Eden Eden Eden draws upon the author’s experiences as a French soldier during the Algerian War of Independence. (He was, notoriously, arrested for inciting desertion and imprisoned in a hole in the ground.) The brutality he witnessed in North Africa propelled Guyotat to develop a form

of writing that refused the association of literature – and the French language – with civilization. Instead, through deformed words, verbal onslaughts and obscene imagery, he has sought to treat language as physical matter, the better to confront the baseness of existence. In its most literal form, Guyotat’s project of literature

as physical substance has involved him masturbating whilst writing.

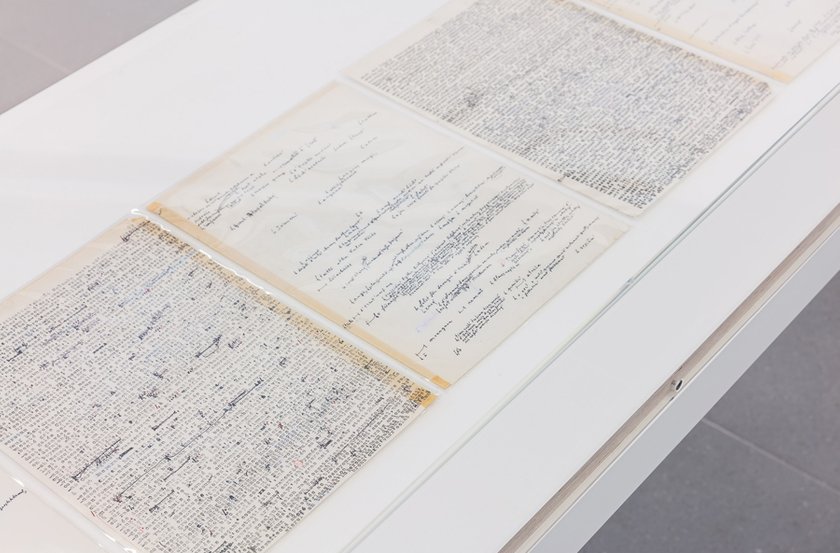

Pierre Guyotat, Le Livre (pages from the manuscript), 1977-1979, pen and ink on paper. Courtesy: Cabinet London and Collection Bibliothèque nationale de France

From early on in his career, Guyotat has exhibited manuscripts and the show at Cabinet is dominated by three large vitrines containing drafts of his 1984 novel Le Livre (The Book). These are peculiar pages: the whole book typed as one continuous paragraph in a single, overwhelming burst of furious energy, disrupted by scribbled redactions and afterthoughts. It’s difficult not to search the page for signs of semen – is that mark simply foxingor a more suspect stain? – or wear and fatigue. (Guyotat’s intensive working practices at one point put him temporarily in a coma.) There could be clearer information on the author’s project of language as matter; anyone coming cold to this reverential display, each page marked with a stamp from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (which holds Guyotat’s archives), might have the false impression that the author sees his writing as sacred rather than profane. To find out more it is necessary to search the folders of supplementary material on the author at the front desk.

Pierre Guyotat, installation view at Cabinet, London, 2017. Courtesy: Cabinet, London

Guyotat’s voice is more faithfully preserved in his reading from Le Livre, which can be listened to by donning headphones. White once said of Guyotat’s dramatic delivery that it made every word sound like he was saying ‘testicles’. In the section I listened to, it sounded more like he had balls in his mouth, with each word difficult to decipher and haltingly delivered in a way that owes something to Antonin Artaud’s 1947 radio play, To Have Done with the Judgement of God.

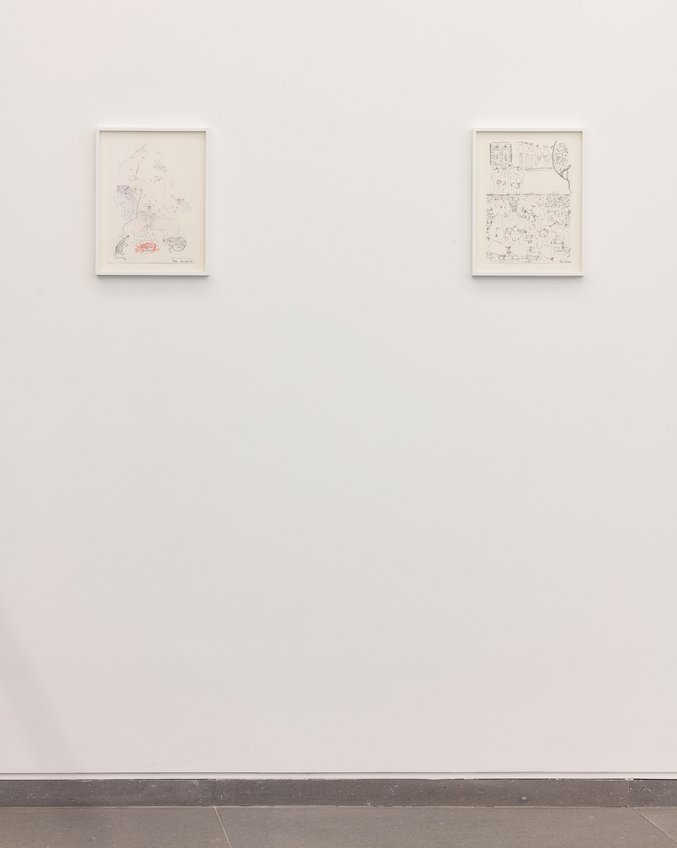

Pierre Guyotat, Drawings, 2016-17, pencil, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 21 x 29 cm. Courtesy: Cabinet, London

Guyotat’s project is perhaps most easily understood in the pen and ink drawings on show, all made in the last two years and marking a return to the medium for the artist after a hiatus of 40 years. A work showing two figures engaging in a sex act has one partner pooling onto the floor, more puddle than person, gnawed at by rats: an unambiguous depiction of man as matter that doesn’t matter. Guyotat’s other great theme – that all life under capitalism, god and government is a form of prostitution and sacrifice to the will of another – is given visceral form in these images. The indistinct, contorted faces of those involved in erotic entanglements obscure whether their labours are enthusiastically or reluctantly undertaken; all pleasure is potentially transactional. If Guyotat’s recent books have become less formally experimental and more reflective, it is in his return to drawing that he pursues his ideas with the full extremity and immediacy of his early work.

Paul Clinton 2017 © Copyright. All Rights Reserved.