Nil Yalter:

Le Chevalier d'Eon

Art Basel, May 2018

By Paul Clinton

Transgender lives are made to conform to a narrative. Despite the burgeoning visibility of trans people over the last half decade, there is a general tendency to represent transitioning as a linear journey with a fixed beginning and end. Born in the wrong body, their real gender waiting to emerge, trans people turn to hormone treatment and surgical intervention to finally become their true self. But this is rarely the whole story: many do not desire surgery, nor do they see their gender as defined by any one role. Nil Yalter’s video installation Le Chevalier d’Eon (1978) undermines this narrative structure. The earliest known work on trans issues by an artist from the Middle East – and a key example of Yalter’s pioneering video art – Le Chevalier challenged the idea that gender identity can or should be so easily narrated and resolved, years before debates about queerness or genderfluidity.

This rejection of linear time notwithstanding, an auspicious set of anniversaries line up to reveal the timeliness of Istanbul-based gallery Galerist’s decision to exhibit the work at Art Basel’s Feature sector in Basel this year. It has been forty years since Le Chevalier was made, and fifty years since the May 1968 protests in Paris, which gave birth to the French gay and women’s liberation movements. Having moved to the city from her native Turkey three years earlier, Yalter was actively involved in this period of civil unrest. She later participated in the feminist artists’ group Femmes en Lutte (Fighting Women).

Le Chevalier also coincides with Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s celebrated In a Year of 13 Moons (1978), a film narrating the last two days in the life of a transgender person. The subject of Yalter’s piece is a former lover who decided to change sex, while Fassbinder’s film was a response to the recent suicide of his boyfriend. Having changed sex, In a Year's protagonist Elvira reverses her decision, but she remains an outcast, rejected by her family and lover. Her ambiguous appearance makes her a non-person in their eyes.

Dislocation and statelessness, the film’s central themes, are equally prominent in Le Chevalier and other well-known works by Yalter. In her video installation Temporary Dwellings (1974-77) – currently hanging in Tate Modern’s permanent collection display – the artist documents migrant communities in Paris, Istanbul, and New York through interviews, location photographs, and the ephemera they leave behind. The impersonal evidence of their lives signals the undecidable state of those who, like Fassbinder’s Elvira, do not belong anywhere. For Fassbinder, Elvira represented a shamed postwar Germany, stripped of its national identity and jilted by all. But if the German filmmaker’s allegory ultimately highlights a phobic version of the transgender narrative, typical of his time, in which the subject is unhappily trapped in a body that can never properly embody any gender, in Le Chevalier, Yalter presents indeterminacy as a radical possibility.

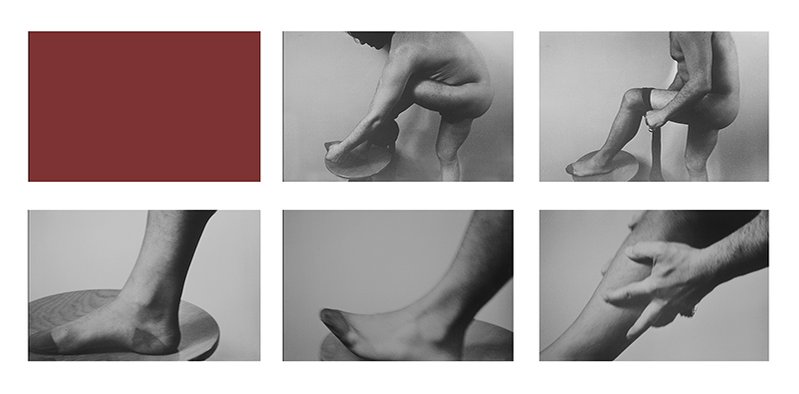

Nil Yalter, Le Chevalier d’Eon, 1978. All images courtesy Galerist, Istanbul.

The video portion of Le Chevalier begins by showing the artist’s former lover as a nondescript middle-aged man, in glasses and turtleneck, staring into camera. Next, it cuts to the same person stripped to the waist, in make-up and earrings, combing and checking their bobbed hair. This presentation of femininity becomes increasingly theatrical in the next few clips where they appear in a chiffon blouse putting on stockings and heels, before donning a lavish fur coat and flirtatiously playing with a boa. But then they appear back in the turtleneck and glasses, hair tied back – a more androgynous Gertrude Stein-type of woman, Yalter was quoted saying. Switching back and forth or amalgamating the masculine and the feminine: this is not a subject willing to believe in gender as a choice between two categories. Indeed, Yalter has remarked that the unnamed protagonist only flirted with hormone treatment for a short while and never wanted to surgically transition. Gender here is a game of fluctuating appearances, with the truth – not only of the video’s subject, but of authentic femininity itself – becoming difficult to locate through the parade of different womanly types.

This play of surfaces and doublings is emphasised by the splitting of the screen into two mirror images that merge in the middle, and at times is pushed to breaking point as further reflections appear in the form of real mirrors and monitors on screen, fragmenting the subject into a mise en abyme. Accompanying photographs underline the depiction of gender as part-fantasy, part-rote practice: two of these images depict the subject in glamorous attire, shot in romantic soft-focus, while black-and-white pictures show cropped representations of hairy chest, torso, and body, alongside side views of the same figure putting on tights.

Nil Yalter, Le Chevalier d’Eon, 1978

The only dialogue occurs in the final scene, where the subject appears in trousers, lying on the floor with a monitor between their legs. On the screen, a pair of lips repeat (in French): ‘Having been an honest man, a zealous citizen, and a brave soldier all my life, I triumph in being a woman and in being able to be cited forever amongst those many women who have proved that the qualities and virtues of which men are so proud have not been denied to those of my sex.’

The line – taken from a biography of the titular Chevalier D’Eon, a real 18th century crossdressing spy and diplomat – underlines the video’s play with the ambiguity of gender and narrative order. The sentence begins as one gender only to become another, while claiming to have been both all along, and confusing the distinctions between the two in the process. What relationship do masculinity or femininity have to biological sex if a woman can have all those qualities thought of as proper to a man?

As the various mirror images fill the screen the one figure not reflected is Yalter herself, and the question of her relationship to this performance of femininity arises. Is her gaze one of desire or identification? What is her position as a feminist in relation to the vampy, idealised, fur-wearing woman? A number of feminists continue to have rocky relationships with its trans sisters. Some feminists have made essentialist claims that to be a woman means to be born as one, accusing transwomen of being men colonising female spaces and perpetuating stereotypes of feminine behaviour. The latter argument perpetuates the erroneous equation between sex and gender, while ignoring that it is the gender identity clinics that so often define what it is to be transgender, making patients conform to various behaviours in order to access treatment.

Nil Yalter, Le Chevalier d’Eon, 1978

A clue to Yalter’s feminist position on trans issues might be found in Le Chevalier’s sibling piece, the video installation Harem (1979-80) made the following year. Again, a single pair of lips speak on a monitor placed between a figure’s legs, but here the voice is multiplied. Comparing the two works, writer Basak Ertür has written that Harem is unambiguously feminist in its representation of a single sex (female) that speaks in many voices. But perhaps, in the model of Luce Irigaray’s French feminist classic This Sex Which is Not One (1977), the claim is even more radically that woman as a singular category has been socially constructed by men, and that this belies the multiple, evolving forms that genders may take. These ideas, stemming from the less transphobic French feminist scene in which Yalter worked, would go on to influence queer theory, with its argument that gender is a performance, not a biological fact.

But Yalter’s work might be more prescient still. For all that queer theories of performativity liberate gender from essentialism, they have been accused of ignoring the body altogether, including the bodies of those who wish to change sex. Are those who surgically transition reinforcing the idea of gender as a fixed state, tied to certain physical attributes? In not distinguishing between stages and styles of transitioning, nor implying a finality to any of them, the artist comes closer to Paul Preciado’s recent claim in Testo Junkie (2008) that bodies do not exist in a natural or permanent state, but are constantly being manipulated by society, industry, and pharmacology. From the discovery of the womb in the 17th century to the invention of the contraceptive pill, the biology of sex is no less historically contingent than gender – trans people who use hormones in non-normative ways are simply appropriating or ‘hacking’ technologies already at work on us all. In this story, as in Le Chevalier, there is no beginning or end, no truth or definition, only a continuing state of being in transit.

Paul Clinton 2017 © Copyright. All Rights Reserved.