Main image:

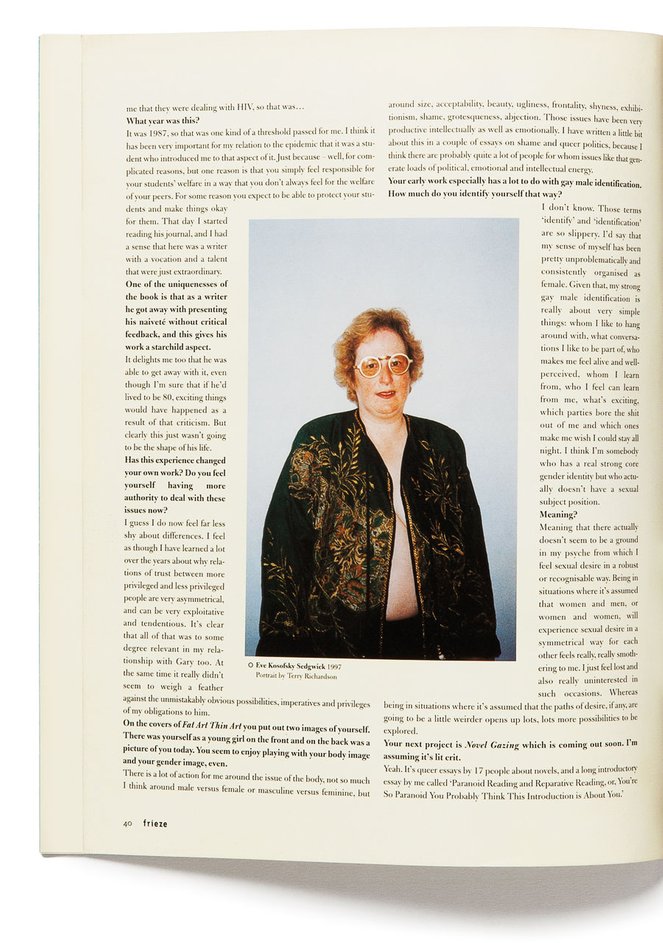

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick photographed by Terry Richardson, 1997, published in frieze issue 34, May 1997.

Photograph: Martina Lang

It’s a queer image in every sense: how did the late Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, a softly spoken academic who Simon Watney described as the ‘primum mobile [prime mover] of queer theory’, come to pose for Terry Richardson, the brash fashion photographer accused of both misogyny and sexual assault? And why was the resulting image published in frieze?

The photograph accompanied a 1997 interview between Sedgwick and Christian Haye; adding to the already dense layers of signification, it was commissioned by Collier Schorr. At that time, Schorr was the magazine’s US editor, but she is perhaps more widely known as a photographer whose work, like Sedgwick’s, often focuses on gender and identity, including male homoeroticism. The image itself is a low-key version of Richardson’s signature bodily and photographic overexposure: Sedgwick appears a little uncomfortable and wary, her round belly and left breast tentatively poking out of her kimono.

She wouldn’t exactly pass for one of Richardson’s more familiar, hyper-sexualized models. Nor, according to Haye, does she look like a radical queer thinker – a circumstance which, he notes, ironically makes her the very personification of queer theory as a ‘politics that is value-based, rather than image-based’.

A few years earlier, Sedgwick had undergone a mastectomy and Schorr thought it would be ‘powerful for Terry to meet this kind of a woman’. If the encounter had any effect on the photographer, it is yet to be discernable in his work.

The portrait had been largely forgotten until my colleague, Matthew McLean, happened upon it in the frieze archives. What is perhaps most striking about the photograph is that it prefigures the two dominant ways in which sexuality tends to be represented in the West today. On the one hand, there is now an increasing openness to queerness and gender variance. On the other, a continued popularization of the pornographic in advertising and fashion imagery has done much to reinforce traditional norms of sex and gender: think of the parodying of porn aesthetics in American Apparel’s Richardson-influenced campaigns, which arguably reproduce the objectification of women that they reference. Perhaps the awkwardness of Richardson’s portrait of Sedgwick signals the disjunction between these two tendencies – Schorr recently told me that she thought that the idea behind the commission was more successful than the result.

Last year saw the 30th anniversary of Sedgwick’s Between Men (1985), the book credited with kick-starting queer theory. In it, Sedgwick marries feminist and gay politics to argue that the bonds between men which enable the oppression of women also enforce the oppression of homosexuality – overt homophobia prevents these male to male relations from appearing homoerotic. Such social arrangements are, she stresses, historically contingent, and in other eras patriarchy has functioned independently of homophobia. Interestingly, in recent years, heterosexist bro culture has become increasingly relaxed about homoeroticism; Richardson, for example, flirts with male celebrities and photographs gay porn stars, drawing upon them for the thrill and power

of transgression but only, of course, at the level of play acting. The shifting nature of these relations indicates that a critique of the kind begun by Sedgwick is as urgent and necessary now as it was 30 years ago.

Paul Clinton 2017 © Copyright. All Rights Reserved.